Introduction: Firstly it is important to point out that habitat fragmentation is an expansive subject, and extensive documentation can be found. Additionally it is important to appreciate that there are other ecological concepts linked with understanding habitat fragmentation. For example, the terms you will come across on the subject include: ecological niche, dispersal rates, habitat corridors, and edge effects.

Where to begin: Firstly what is an ecological niche? The concept of an ecological niche is actually not that complex, once you have a grasp on where the animal or plant lives, and how it interacts within its community. In other words the food/nutrients it needs, or the shelter it needs, which will be unique to that species. That in essence is its ecological niche. It is in this respect that niche and habitat are not the same, because many different species can share a habitat, however this is not true of a niche.

To find out more about this fascinating subject follow: Darwin’s Speciation Theory & Speciation.

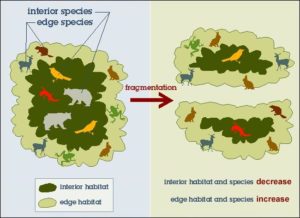

What is habitat fragmentation? the term habitat fragmentation is focused on the disruption of large continuous chunks of habitat, which have become divided and subdivided into smaller ‘fragments’ of habitat, which are either completely isolated from each other (as the image below demonstrates), or destroyed altogether through additional development. These fragments are rarely indicative of the original environment. Once the habitat is lost, it cannot be restored to what is once was, meaning it can no longer fill the same ecological purpose.

Habitat fragmentation is of primary concern especially in conservation biology. Some species have evolved to rely upon a specific habitat type or even food source(s), (as explained by the term ecological niche) and once this habitat has been altered it no longer offers them a suitable environment, primarily because it is not able to provide enough food and shelter. The theory is that environmental changes, such as environments damaged by human activity, prompt species to adapt to these new conditions or changes. Some examples include habitat destruction, habitat fragmentation or pollution.

What causes it? Humans often change the environment through clearing native vegetation for agriculture, rural development, and urbanisation, thus destroying large continuous chunks of habitat.

What effect does it have? Plants and animals are often directly destroyed as a result. It is often the speed at which we change the environment that makes it impossible for those species left to adapt. Species unable to adapt to these changes in their environment have no choice but to either migrate to a more suitable habitat, or face a reduced population, which in some cases could lead to extinction. Some species are more vulnerable to this than others. For example species which have specialised ecological niche requirements. Quite simply habitat fragmentation can effect occupancy, reproduction, or even survival in a particular species.

Additionally some species require more than one habitat type, and part of their survival relies upon seasonal migration. Any species that cannot cross what to them is a physical barrier, thus preventing their normal pattern of movement, also face the harsh prospect of extinction. Examples of these barriers include roads, fields of crops, (due to such an open environment the risk of predation is high) housing developments, industrial construction, towns, or even fences.

Those species which are more mobile, retreat into these patches of habitat. However, this causes additional pressures in the form of increased competition, and a reduced gene pool. Smaller fragments of habitat support smaller populations which are therefore more vulnerable to extinction. These smaller fragments also exhibit what is known as the edge effect.

This reduces further the amount of suitable habitat remaining in a fragment. For example, the edge of a woodland offers quite a different habitat than the centre of a woodland, and may not be suitable for some species, largely due to an increased threat of predation. Other factors which may make the edge inhospitable to some species may include the amount of light, temperature, wind, and even noise that they experience.

It could be said the most disastrous consequence of habitat fragmentation is a loss of biodiversity of native species. As mentioned in a previous blog, biodiversity is highly beneficial to humans in terms of a healthy ecosystem, thus providing us with resources, which we so rely upon.

What can I do? The aim of this blog is to inspire garden owners and garden designers to think about creating ‘habitat corridors’ within gardens. They are by no means a new theory, but are people actually aware of their importance? To put this into context, it is estimated that there are some 15 million gardens in Britain.

If we created habitat corridors in our gardens connecting adjacent habitats and neighbouring gardens, we would hopefully reduce the fragmentation effect by increasing the possibility of species being able to move freely between suitable habitats.

Additionally if we use habitat corridors to link up different areas within our gardens, (such as herbaceous borders, lawn, meadow and hedges), this can potentially increase both availability and access to these habitats, for many species.

Although it will not reduce the edge effect, and is certainly no substitution for the environments we have fragmented, it will hopefully go some way in helping to counteract the effects of fragmentation.